Quick Takeaways

- Medication errors are preventable mistakes in the prescribing‑to‑administration chain.

- Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) happen when a correctly administered drug harms the patient.

- Side effects are a predictable subset of ADRs that are not the intended therapeutic outcome.

- Use a five‑step algorithm to tell them apart at the bedside.

- Barcode scanning, CPOE, and AI‑driven note analysis cut errors by up to 75% in modern hospitals.

What Exactly Is a Medication Error?

Medication errors are any preventable events that could cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the drug is in the control of a health‑care professional, patient, or consumer. The World Health Organization first defined the term in 2002 and refined it in 2019 with input from the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH E2D). In practice the error can happen at any of the nine steps from prescribing to monitoring.

Common error types include:

- Incorrect dose (32.7% of all errors in a 2023 AHRQ report).

- Wrong route - e.g., IV instead of oral (7.3% of errors, 3.8% mortality).

- Expired product (1.2% of dispensing incidents).

- Incorrect timing (11.4% of all errors that affect outcomes).

Adverse Drug Reactions and Side Effects - How They Differ

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are harmful responses that occur at normal doses during normal use. The WHO has used this definition since 1972. ADRs split into two categories:

- Type A (dose‑dependent): predictable, accounting for about 80% of ADRs (Lazarou et al., 2021).

- Type B (idiosyncratic): unpredictable, immune‑mediated, about 15% of ADRs with a 5‑10% mortality rate.

Side effects are the predictable, non‑intended reactions that fall under Type A. The FDA now prefers the term “adverse drug reaction” to avoid normalising harm. Examples include drowsiness from antihistamines or the hair‑growth effect of minoxidil, which can be repurposed therapeutically.

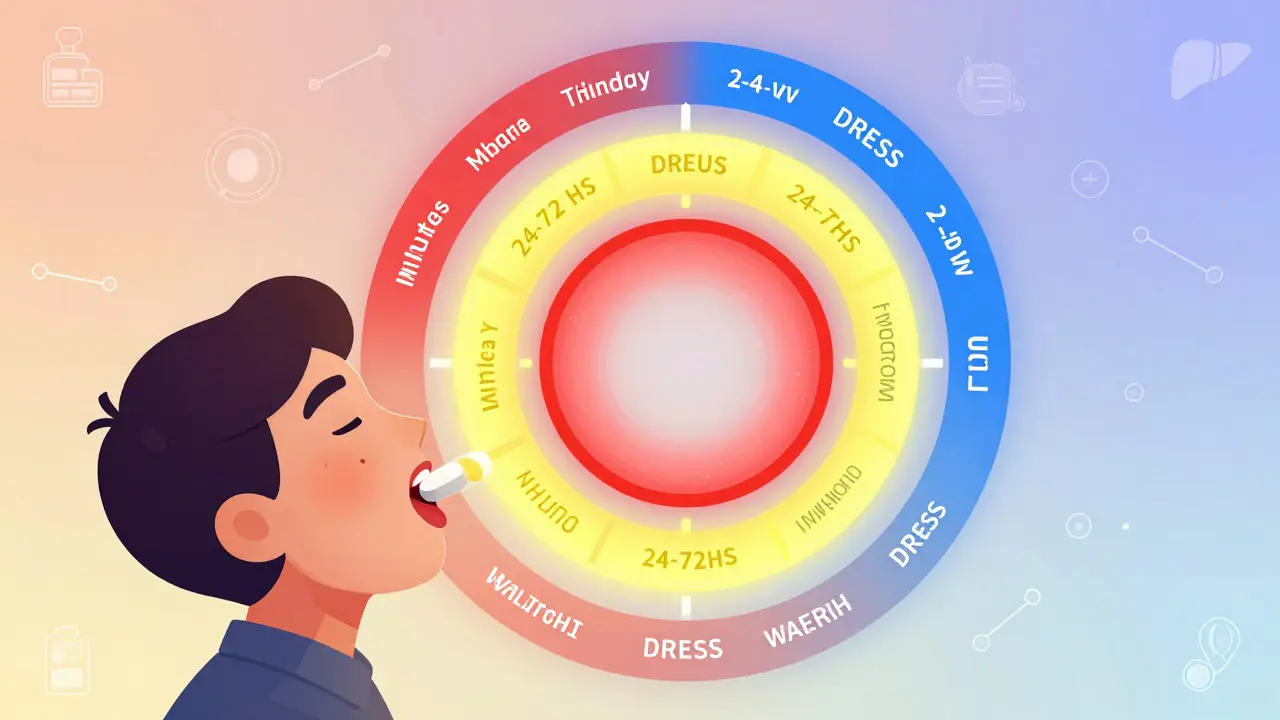

Five‑Step Algorithm to Distinguish Errors from ADRs

- Did harm occur? If no injury, you are dealing with a near‑miss or potential error.

- Was the medication given exactly as prescribed? Any deviation (dose, route, timing) signals a medication error.

- Is the reaction predictable for that drug? Consult the drug’s label or FDA’s medication guide. Predictable → side effect.

- Is the reaction dose‑dependent? If yes, it is a Type A ADR; if no, consider Type B.

- Are patient‑specific factors (allergies, genetics) likely contributors? If the answer is yes and the drug was correct, you are dealing with an ADR.

This framework mirrors the AHRQ 2023 Medication Error Identification Toolkit and has been shown to improve correct classification by 18% in pilot hospitals.

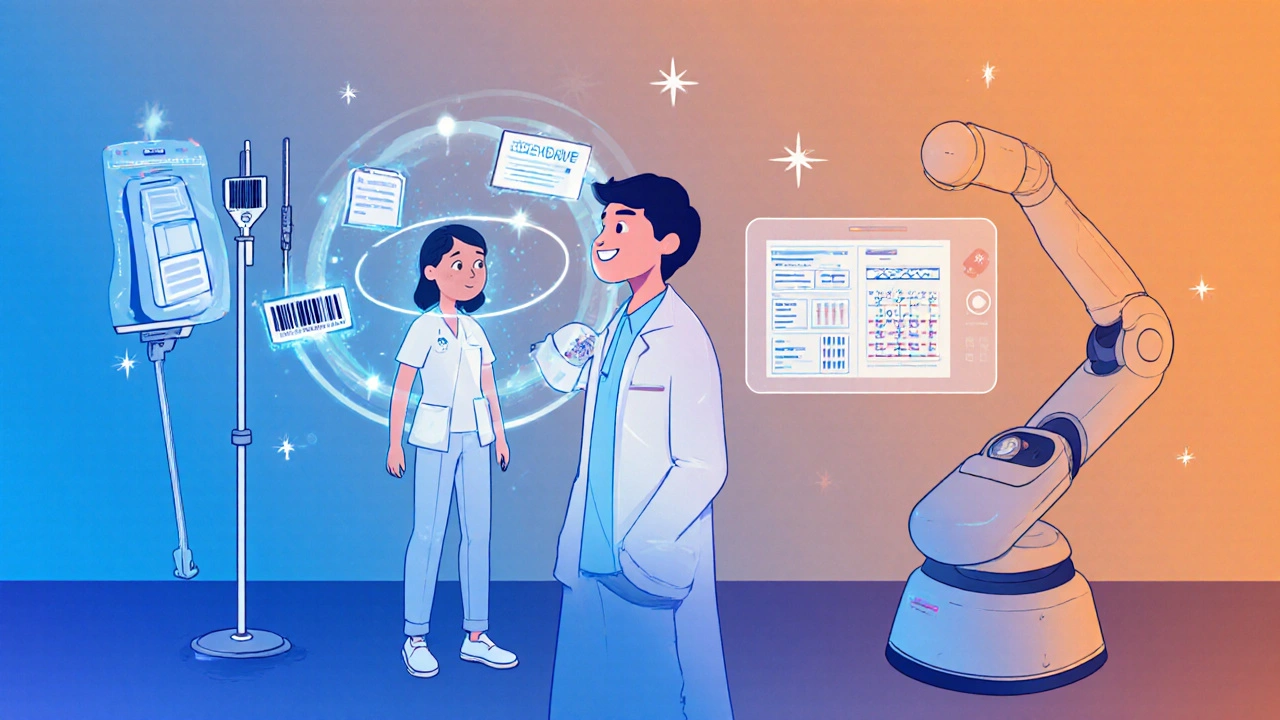

Technology that Helps Spot the Difference

Smart tools reduce preventable errors dramatically:

- Barcode medication administration scans cut administration errors by 57% (AHRQ, 2022).

- Computerized Provider Order Entry (CPOE) with clinical decision support is in use at 92.7% of U.S. hospitals, flagging dose‑range violations before the order is signed.

- AI‑driven natural‑language processing (NLP) in Epic’s 2024 medication safety module correctly tags errors vs ADRs with 89.7% accuracy (JAMIA, 2023).

- The WHO‑Uppsala Monitoring Centre’s Global ADR Signal Detection System uses machine learning to separate true ADR signals from error‑induced noise.

Even with these advances, a 2023 AHRQ study found only 38.7% of organisations have fully integrated error and ADR reporting, leaving a large under‑reporting gap.

Reporting, Documentation, and the Language Issue

Accurate coding matters for patient safety and for reimbursement. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) recommends using adverse drug reaction instead of “side effect” in incident reports. Mislabeling an error as a side effect-something 68% of nurses admit doing-skews data and hampers quality‑improvement efforts.

Standardised causality assessment (WHO‑UMC criteria) is required for ADR reporting, while the NCC MERP taxonomy guides error classification from “Category A” (circumstances that could cause error) to “Category I” (error that contributed to or resulted in patient death).

Real‑World Cases That Show Why the Distinction Matters

Case 1 - Vancomycin nephrotoxicity: The drug level was not monitored per protocol, leading to an overdose. The resulting kidney injury was initially filed as a side effect, delaying system‑level corrections. After re‑classification as a medication error, the hospital introduced automated trough‑level alerts, cutting similar events by 42%.

Case 2 - Minoxidil hair growth: Patients using the drug for hypertension reported unexpected hair growth. Because the reaction was predictable, it was logged as a side effect and later repurposed as a treatment for alopecia, showing how side effects can become therapeutic.

Case 3 - Insulin dosing error: A decimal‑point mistake (10 U vs 1.0 U) caused severe hypoglycaemia. The error was caught by barcode scanning at bedside, and a root‑cause analysis led to a double‑check policy for high‑risk insulin orders.

Checklist for Clinicians - Quick Decision Aid

- Verify the prescription matches the administration record.

- Ask: Is the patient’s reaction listed in the drug’s approved label?

- Check dose‑range alerts in CPOE.

- Document using WHO‑UMC criteria for ADRs or NCC MERP categories for errors.

- Report to your institution’s safety board within 24 hours.

Keep this list on your work‑station; a simple pause can turn a potential error into a learning moment.

Future Outlook - Where Is the Field Heading?

By 2028, pharmacogenomic testing is projected to cut preventable ADRs by 35‑40% for high‑risk meds. Closed‑loop medication systems (integrating barcode, CPOE, and AI alerts) aim for a 75% reduction in errors by 2030. Yet, the National Academy of Medicine warns that polypharmacy in the elderly could offset these gains unless we redesign workflows holistically.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main difference between a medication error and an adverse drug reaction?

A medication error is a preventable mistake in the prescribing, dispensing, or administering process. An adverse drug reaction occurs even when the drug is given exactly as intended; it is a harmful response to a correctly administered medication.

Are side effects the same as adverse drug reactions?

Side effects are a predictable subset of adverse drug reactions that are not the therapeutic goal. The FDA now recommends calling them adverse drug reactions to avoid down‑playing the risk.

How can I quickly tell if a patient’s problem is an error or an ADR?

Use the five‑step algorithm: check for harm, confirm the medication matched the order, assess predictability, evaluate dose‑dependence, and consider patient‑specific factors.

What technology should my clinic adopt to reduce medication errors?

Barcode medication administration, CPOE with decision support, and AI‑enabled clinical note analysis are the top three tools backed by recent studies.

Why does accurate terminology matter in incident reporting?

Mislabeling errors as side effects skews safety data, delays system‑wide fixes, and can affect reimbursement. Using the correct terms (error vs ADR) ensures the right quality‑improvement actions are taken.

medication errors are more than a paperwork issue-they’re a safety signal that, when identified correctly, can save lives and billions of dollars.

Sarah Keller on 25 October 2025, AT 12:13 PM

Mistakes kill; get the tech working now.