Every year, millions of people end up in hospitals not because their illness got worse, but because the drugs meant to help them made things worse. These aren’t mistakes - they’re predictable outcomes of how our genes interact with medications. This is where pharmacogenomics comes in. It’s not science fiction. It’s a real, growing field that’s changing how we think about drug safety - especially when multiple medications are involved.

Why Your Genes Matter More Than You Think

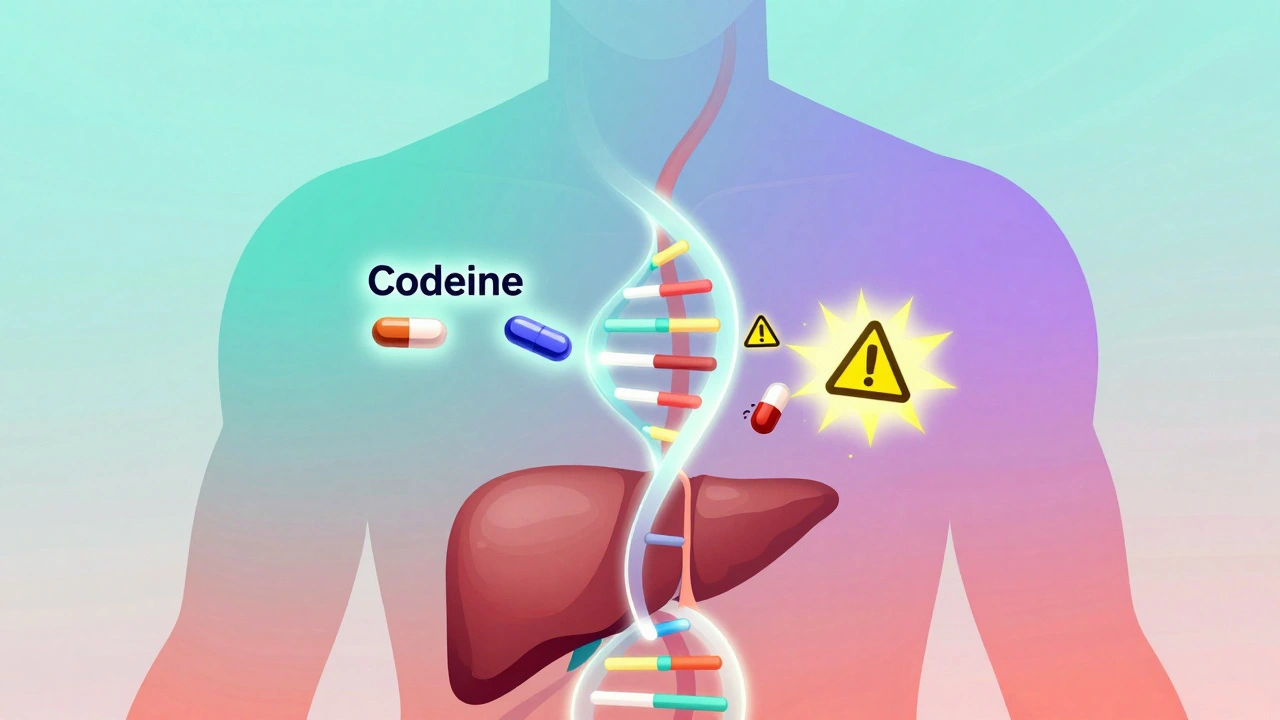

Most people assume that if a drug is prescribed correctly, it will work the same way for everyone. But that’s not true. Two people can take the exact same dose of the same drug, and one might feel fine while the other ends up in the ER. Why? Because of differences in their DNA. Your body uses enzymes to break down drugs. These enzymes are made based on instructions in your genes. Some people have versions of these genes that make enzymes work too fast. Others have versions that barely work at all. For example, the CYP2D6 gene controls how your body processes about 25% of commonly used drugs - including antidepressants, painkillers like codeine, and antipsychotics. If you’re a poor metabolizer (because of your genes), codeine won’t turn into its active form, so it won’t relieve pain. If you’re an ultra-rapid metabolizer, codeine turns into morphine too quickly, risking overdose. This isn’t rare. About 7% of people of European descent are poor metabolizers of CYP2D6. In some Asian populations, that number jumps to 20%. These genetic differences don’t show up on a blood test unless you specifically look for them. But they’re always there - quietly shaping how your body handles every pill you take.Drug Interactions Get Worse When Genes Are Ignored

Traditional drug interaction checkers - the kind pharmacists use - look at two drugs at a time. They’ll warn you if, say, an antibiotic and a blood thinner shouldn’t be taken together. But they don’t know your genes. That’s like trying to drive with blinders on. Enter drug-drug-gene interactions (DDGIs). These happen when two drugs interact in a way that’s made worse - or better - by your genetics. For example:- You’re taking fluoxetine (an antidepressant) and metoprolol (a beta-blocker). Fluoxetine blocks the CYP2D6 enzyme. If you’re already a poor metabolizer because of your genes, metoprolol builds up in your system, increasing the risk of slow heart rate or low blood pressure.

- You’re on warfarin (a blood thinner). Your CYP2C9 gene affects how fast you break it down. Your VKORC1 gene affects how sensitive your body is to it. If your doctor doesn’t know your genetic profile, they might give you a dose that’s too high - leading to dangerous bleeding.

The Real Cost of Ignoring Genetics

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) aren’t just uncomfortable - they’re expensive. In the U.S. alone, they cost the healthcare system about $30 billion every year. About 30% of those reactions happen in people taking five or more medications - a group that’s grown to 13% of American adults. Pharmacogenomics cuts through the noise. For example:- Patients with a TPMT gene variant who take azathioprine (used for autoimmune diseases) can develop life-threatening bone marrow suppression if given a standard dose. Genetic testing lets doctors reduce that dose to 10% of normal - avoiding disaster.

- People with the HLA-B*15:02 gene variant who take carbamazepine (for seizures or nerve pain) have up to 100 times higher risk of a deadly skin reaction called Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Screening for this variant before prescribing is now standard in many countries.

What’s Being Done - and What’s Still Missing

The good news? We have guidelines. The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) has published over 100 evidence-based recommendations for how to adjust doses based on genetic test results. The FDA lists 148 gene-drug pairs with clinical implications - including clear warnings for drugs like clopidogrel, statins, and certain cancer therapies. Some hospitals are ahead of the curve. Mayo Clinic has been testing patients preemptively since 2011. They found that 89% of patients had at least one gene-drug interaction that could be avoided with better dosing. Their system now automatically flags risky prescriptions in the electronic record - and it reduced inappropriate prescribing by 45%. But most places aren’t there yet. Only 15% of U.S. healthcare systems have integrated genetic data into their electronic health records. Community pharmacists - the frontline for checking drug interactions - report that only 28% feel confident interpreting genetic results. And even when tests are done, insurance often won’t pay for them. With only 19 specific billing codes for pharmacogenomic testing and reimbursement averaging $250-$400 per test, many providers can’t justify the cost. There’s also a serious gap in research. Over 98% of pharmacogenomic studies have been done in people of European or Asian ancestry. African, Indigenous, and Latino populations are drastically underrepresented. That means the guidelines we have may not work well for everyone. A gene variant common in one group might be rare or even absent in another - and we’re still learning what that means.The Future Is Personal - But It Needs to Be Fair

The tools are getting better. AI models that combine genetic data with drug profiles are now predicting warfarin dosing 37% more accurately than older methods. The NIH’s All of Us program has returned PGx results to over 250,000 people. The FDA plans to add 24 new gene-drug pairs to its list in 2024. But technology alone won’t fix this. We need:- More training for doctors and pharmacists - not just on how to read reports, but how to explain them to patients.

- Standardized testing across labs - right now, two different labs might call the same gene variant by different names.

- Better insurance coverage - if testing costs $400 and saves $10,000 in hospital bills, why aren’t insurers paying?

- Inclusive research - we can’t build a system that works for everyone if we only studied half the population.

What You Can Do Today

If you’re on multiple medications - especially for chronic conditions like depression, heart disease, or pain - ask your doctor: “Could my genes affect how these drugs work?” You don’t need to wait for a full genetic test. Some drug labels already include pharmacogenomic warnings. Check the prescribing information for your medications - you can find them on the FDA website or ask your pharmacist. If you’ve had a bad reaction to a drug in the past - even if it was years ago - that’s a red flag. It could be your genes. Don’t dismiss it as “bad luck.” And if you’ve done a direct-to-consumer genetic test like 23andMe - don’t ignore the drug response reports. They’re limited, but they can be a starting point. Bring them to your doctor. Don’t make changes on your own, but do ask: “Is this something we should look into?”Bottom Line

Pharmacogenomics isn’t about predicting the future. It’s about preventing the past from repeating. Every time we prescribe a drug without knowing a patient’s genetic profile, we’re gambling with their safety. And when multiple drugs are involved - as they often are - the odds get worse. The science is solid. The tools exist. The evidence shows it works. What’s missing is the will to use it - everywhere, for everyone.What is pharmacogenomics?

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how your genes affect how your body responds to medications. It helps explain why some people have bad side effects or no effect at all from drugs that work well for others. This field uses genetic testing to guide safer, more effective dosing.

Can pharmacogenomics prevent all drug interactions?

No, but it prevents many of the most dangerous ones. It’s especially powerful for interactions involving metabolism enzymes like CYP2D6 and CYP2C19. It won’t catch interactions caused by kidney or liver disease, or by food and supplements - but it adds a crucial layer of safety that traditional drug checkers miss.

Which drugs are most affected by pharmacogenomics?

Antidepressants (like SSRIs), painkillers (codeine, tramadol), blood thinners (warfarin), anti-seizure drugs (carbamazepine), and certain cancer drugs (like 5-FU and tamoxifen) are among the most influenced by genetics. These drugs have well-documented gene-drug pairs with clear dosing guidelines.

Is pharmacogenomic testing covered by insurance?

Sometimes. Medicare and some private insurers cover testing for specific drugs like warfarin or clopidogrel when there’s a clear clinical need. But routine preemptive testing - where you get tested before any prescription - is rarely covered. Costs range from $250 to $400, and without insurance, many patients pay out of pocket.

Should I get tested if I’m on just one medication?

It depends. If you’ve had an unexpected side effect, or if the drug you’re taking has a known pharmacogenomic warning (like codeine or clopidogrel), testing could be very useful. For most people on a single, low-risk medication, it’s not urgent - but it could still provide valuable insight for future prescriptions.

Are direct-to-consumer tests like 23andMe reliable for drug safety?

They can be a starting point, but they’re not complete. 23andMe tests for a few key variants (like CYP2D6 and CYP2C19), but not all that matter. Their reports are designed for education, not clinical use. Always bring results to a doctor or pharmacist who can interpret them in context with your full medication list.

Why aren’t all doctors using pharmacogenomics yet?

Several reasons: lack of training, no integrated systems in electronic health records, unclear reimbursement, and slow adoption in community clinics. Most doctors learned medicine before pharmacogenomics was part of standard curriculum. It’s changing - but slowly.

Dematteo Lasonya on 4 December 2025, AT 01:19 AM

I’ve been on three meds for years and never thought about my genes playing a role. This post made me realize my weird reaction to codeine wasn’t just bad luck - it was biology. I’m getting tested next week.