If you’re taking acitretin for psoriasis or another skin condition, you might have heard whispers about bone problems. Is it real? Or just another scare story online? The truth is, acitretin can affect your bones - and it’s not something you can ignore.

What is acitretin, really?

Acitretin is a retinoid, a synthetic form of vitamin A. It’s not a steroid. It’s not an antibiotic. It’s a powerful drug designed to slow down how fast skin cells grow - which is why it works so well for severe psoriasis, especially pustular or erythrodermic types. It’s usually taken as a capsule once a day, often after a meal to help with absorption.

It’s not a first-line treatment. Doctors don’t hand it out like aspirin. You’re typically prescribed acitretin only after other treatments - like topical creams, light therapy, or methotrexate - have failed. And because it’s so strong, you need regular blood tests to check liver function and cholesterol levels.

But here’s the part most patients don’t know: acitretin doesn’t just mess with your skin. It also interferes with how your body builds and breaks down bone.

How acitretin messes with your bones

Your bones are alive. They’re constantly being broken down by cells called osteoclasts and rebuilt by osteoblasts. This balance keeps your skeleton strong. Acitretin throws this balance off.

Studies from the 1990s and early 2000s - including ones published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology and Archives of Dermatology - showed that people on long-term acitretin therapy had higher levels of bone resorption markers. That means their bones were breaking down faster than they were rebuilding.

One 1998 study followed 32 patients on acitretin for up to two years. Nearly half showed measurable bone mineral density loss, especially in the spine and hips. Another study in 2001 found that acitretin users had significantly higher rates of hyperostosis - abnormal bone growth - particularly around the spine and ligaments. That’s not the same as osteoporosis, but it’s another sign your skeleton is being affected.

It’s not just about density. Acitretin also increases calcium levels in your blood. That sounds good, right? But too much calcium circulating can cause your body to pull it out of your bones to compensate - leaving them weaker over time.

Who’s at the highest risk?

Not everyone on acitretin will develop bone problems. But some people are far more vulnerable.

- Women over 50 - especially those already postmenopausal. Estrogen helps protect bone density. When estrogen drops, bones become more sensitive to drugs like acitretin.

- People with a history of osteoporosis - if your bones are already fragile, acitretin can make things worse fast.

- Long-term users - taking acitretin for more than a year increases risk. The longer you’re on it, the more time your bones have to deteriorate.

- Those with low vitamin D or calcium intake - if you’re not getting enough of these nutrients, your body has nothing to rebuild with.

- People who smoke or drink alcohol - both habits damage bone health independently. Add acitretin, and the damage multiplies.

One real case from a Perth dermatology clinic in 2023 involved a 58-year-old woman who’d been on acitretin for 18 months for plaque psoriasis. She developed sudden lower back pain. A DEXA scan showed her spine bone density had dropped 14% in just over a year. She’d never had a fracture before. She stopped acitretin, started calcium and vitamin D, and began weight-bearing exercise. Her bone density stabilized - but she lost nearly a year’s worth of bone strength.

What your doctor should be doing

Good doctors don’t just write a prescription and forget about it. If you’re on acitretin, you should be getting baseline bone health screening before you start.

That means:

- A DEXA scan to measure bone mineral density (BMD) - especially if you’re over 45 or have risk factors.

- Blood tests for calcium, vitamin D, and parathyroid hormone.

- A review of your lifestyle - diet, smoking, alcohol, exercise.

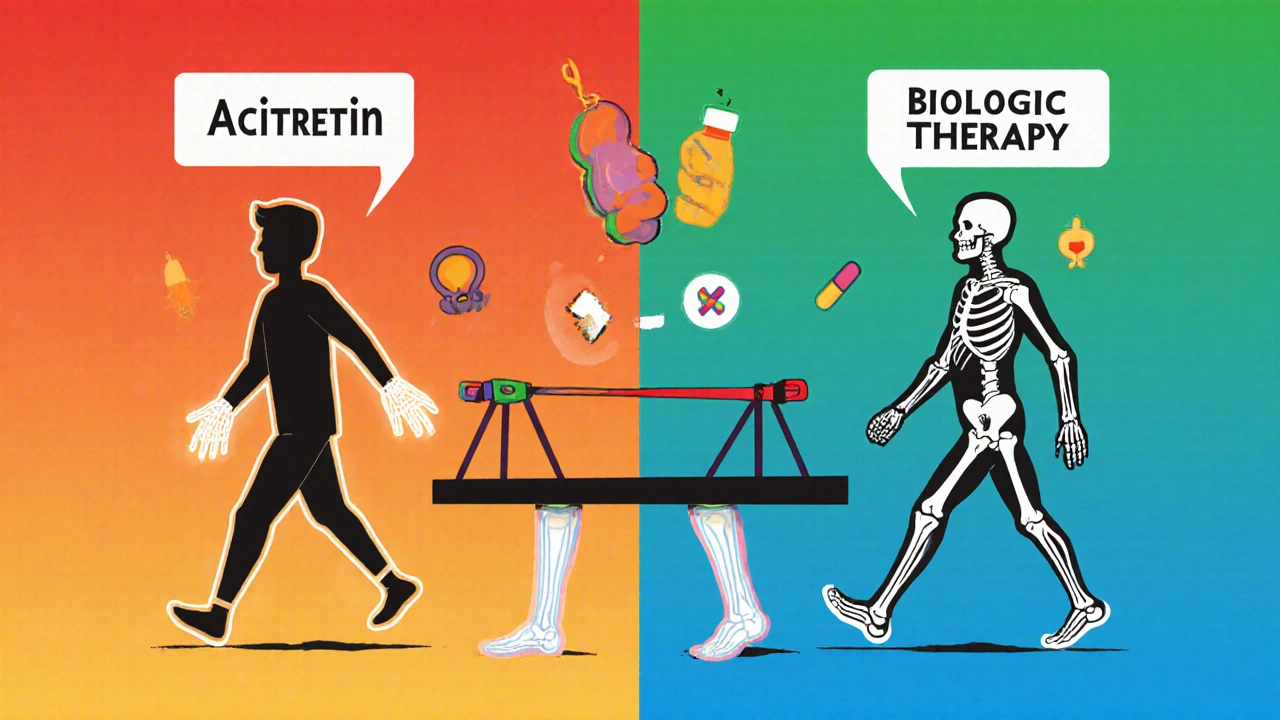

After starting acitretin, you should get a follow-up DEXA scan after 12 months. If your bone density is dropping, your doctor may switch you to another treatment - like a biologic - or add bone-protecting meds like bisphosphonates.

Many patients don’t know this. They assume if their skin is clearing up, everything’s fine. But skin improvement doesn’t mean your bones are safe.

Can you protect your bones while on acitretin?

Yes - but you have to be proactive. You can’t just wait for symptoms to show up.

Here’s what actually works:

- Take 1,200 mg of calcium daily - from food or supplements. Dairy, leafy greens, fortified plant milks, and canned fish with bones (like sardines) are good sources.

- Get 800-1,000 IU of vitamin D daily - especially if you live in Perth, where winter sun exposure drops. Many people here are deficient, even in summer.

- Do weight-bearing exercise - walking, stair climbing, resistance training. Just 30 minutes, 4 times a week, helps your bones stay dense.

- Avoid smoking and limit alcohol - both are proven bone killers.

- Ask about bone density monitoring - don’t wait for pain. Get tested.

One 2020 study in the British Journal of Dermatology showed that patients who took calcium and vitamin D supplements while on acitretin had no significant bone loss over two years - while those who didn’t, lost an average of 5% in hip density.

What if you already have osteoporosis?

If you’ve already been diagnosed with osteoporosis, acitretin is usually avoided. But if your skin condition is severe and no other treatments work, your dermatologist and endocrinologist might work together to manage the risk.

Options include:

- Switching to a biologic like secukinumab or ustekinumab - these don’t affect bone density.

- Starting a bone-protecting drug like alendronate or denosumab before beginning acitretin.

- Using the lowest possible dose of acitretin for the shortest time.

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. But you can’t just push through. Bone loss from acitretin is often silent - and irreversible.

How long does acitretin stay in your system?

One big myth is that once you stop acitretin, your bones bounce back. That’s not always true.

Acitretin has a very long half-life - up to 120 days. And its metabolites can linger even longer. That means the bone effects don’t stop the day you take your last pill. Bone remodeling takes months. So even after stopping, you need to keep monitoring your bone health for at least a year.

Some patients report ongoing bone pain or stiffness for months after discontinuing acitretin. That’s not normal, and it’s not just "old age." It’s a sign your bones are still recovering.

What are the alternatives?

If you’re worried about your bones, there are other options for severe psoriasis:

- Biologics - like adalimumab, etanercept, or secukinumab. These target specific parts of the immune system. No known effect on bone density.

- Methotrexate - can be hard on the liver, but doesn’t typically cause bone loss. Often used long-term.

- Phototherapy - UVB light therapy. No systemic side effects. Works well for moderate cases.

- Topical treatments - calcipotriol, tazarotene, or corticosteroid creams. Not for widespread disease, but good for maintenance.

Biologics are expensive. But if you’re at risk for osteoporosis, the cost of a broken hip or spine fracture is far higher - in money, pain, and quality of life.

Bottom line: Don’t ignore your bones

Acitretin works. It clears skin. But it’s not harmless. Bone health isn’t a side note - it’s a core risk. If you’re on this drug, you need to treat your bones like a patient - because they are.

Get tested. Take supplements. Move your body. Talk to your doctor - not just about your skin, but about your skeleton. If you’re over 45, female, or have any risk factors, don’t wait for pain. Ask for a DEXA scan now.

Your skin might look better. But if your bones break, you’ll wish you’d paid attention sooner.

Can acitretin cause osteoporosis?

Yes, long-term use of acitretin can lead to decreased bone mineral density, especially in postmenopausal women, older adults, and those with pre-existing bone conditions. Studies show measurable bone loss after 12-24 months of treatment, particularly in the spine and hips.

How do I know if acitretin is affecting my bones?

You won’t feel it until damage is advanced. The only way to know is through a DEXA scan - a simple, non-invasive X-ray that measures bone density. If you’ve been on acitretin for over a year, ask your doctor for one. Blood tests for calcium and vitamin D can also help assess risk.

Can I take calcium and vitamin D while on acitretin?

Yes, and you should. Most experts recommend 1,200 mg of calcium and 800-1,000 IU of vitamin D daily for people on acitretin. These nutrients help counteract the bone-thinning effects. Always check with your doctor first - especially if you have kidney issues.

How long after stopping acitretin should I keep monitoring my bones?

Even after stopping acitretin, its effects can linger for months. Bone remodeling takes time, and bone density loss may continue for up to a year. It’s wise to get a follow-up DEXA scan 12 months after stopping treatment - especially if you had low bone density while on the drug.

Are there safer alternatives to acitretin for psoriasis?

Yes. Biologics like secukinumab, ustekinumab, and adalimumab are effective for severe psoriasis and don’t affect bone density. Methotrexate and phototherapy are also options. The best alternative depends on your overall health, severity of psoriasis, and insurance coverage. Talk to your dermatologist about switching if bone health is a concern.

Craig Venn on 31 October 2025, AT 19:53 PM

Acitretin's effect on bone remodeling is well documented in dermatology literature but underdiscussed in clinical practice. Osteoclast activation via retinoid receptor signaling leads to uncoupled bone turnover. Baseline DEXA scans should be standard before initiation, not optional. Vitamin D levels below 30 ng/mL are a contraindication. Calcium supplementation alone won't cut it if you're not addressing the underlying resorption cascade. Biologics like IL-17 inhibitors have zero bone toxicity and are now first-line for moderate-severe psoriasis in patients over 45. Stop treating this like a skin-only issue.