When you fill a prescription for a brand-name drug, your pharmacist may be legally allowed to give you a cheaper generic version instead. In most U.S. states, that’s not just allowed-it’s required unless your doctor says otherwise. But what if the drug company makes it impossible for that substitution to happen? That’s not just bad luck-it’s a legal tactic many companies have used to keep prices high, and it’s drawing serious attention from regulators.

How Generic Substitution Is Supposed to Work

The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act created the modern system for generic drugs. It let companies make copies of brand-name medications once patents expired, as long as they proved they worked the same way. The idea was simple: lower prices, more access. But there’s a critical piece most people don’t think about: state pharmacy laws that let pharmacists automatically swap in generics.

These laws aren’t optional. In states like New York, California, and Illinois, pharmacists must substitute unless the prescriber blocks it. That means if you’re on a brand-name drug that just lost its patent, your pharmacist can-and often will-give you the generic version without calling your doctor. This system works because generics are cheaper, and patients don’t need to re-learn how to take their medicine. But drug companies realized something: if they can block this automatic switch, they can keep selling their expensive brand-name version for months or even years longer.

Product Hopping: The Main Antitrust Tactic

The most common trick is called product hopping. It’s not innovation-it’s manipulation.

Here’s how it works: A company has a drug with a patent about to expire. Instead of letting generics take over, they introduce a slightly different version-maybe a new pill shape, a time-release formula, or a different dosage. Then they pull the original version off the market. Suddenly, your pharmacist can’t substitute the generic because the version it was designed to replace no longer exists.

The classic example is Namenda, a drug for Alzheimer’s. Actavis made an immediate-release version (Namenda IR). When the patent neared expiration, they launched Namenda XR, an extended-release version, and pulled Namenda IR from shelves just 30 days before generics could enter. The result? Doctors couldn’t write prescriptions for the original, and pharmacists couldn’t switch. Patients were forced onto the new version, which was still under patent protection. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals called this out in 2016: “It’s not competition-it’s exclusion.”

It’s not just Namenda. Teva did the same with Copaxone, switching from a daily injectable to a new formulation. Consumers paid an extra $4.3 to $6.5 billion over two and a half years before courts finally ruled against them. The new version offered no real benefit-just enough of a change to reset the patent clock.

Why This Violates Antitrust Law

Antitrust law exists to stop monopolies from using tricks to crush competition. When a company pulls its original product before generics can enter, it’s not just protecting its patent-it’s destroying the entire system designed to bring down prices.

State substitution laws are the main tool generics have to compete. Without them, generics would need to spend millions on advertising, convince doctors to prescribe them, and convince patients to switch-all while the brand-name drug still dominates. That’s not fair competition. That’s a rigged game.

The FTC’s 2022 report made this clear: “Product hopping strategies often lack procompetitive justification.” In other words, these moves don’t improve patient care. They just delay savings. Courts that have ruled against this practice-like in the Namenda and Suboxone cases-have recognized that when a company removes the original product, it’s not offering a better alternative. It’s eliminating the only path generics have to reach patients.

Other Tactics: REMS Abuse and Coercion

Product hopping isn’t the only trick. Some companies use FDA-mandated safety programs called Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) to block generics.

REMS are meant to manage serious side effects-for example, drugs that can cause birth defects. But some brand-name companies abuse them. They refuse to sell samples of their drug to generic manufacturers, claiming safety concerns. Without those samples, generics can’t run the tests needed to prove their version works the same. This delays approval by years.

According to legal scholar Michael A. Carrier, over 100 generic companies have reported being blocked this way. A study of 40 drugs with restricted access showed this tactic cost consumers more than $5 billion a year. The FTC calls it “a textbook case of monopolization.”

Another tactic? Fear. In the Suboxone case, Reckitt Benckiser pushed patients away from tablets and toward film strips. They spread claims that the tablets were unsafe-even though there was no evidence. They threatened to pull the tablets from the market. The court found this was coercion: patients didn’t choose the film-they were forced into it.

What Courts Have Said: A Patchwork of Rulings

Not all courts see it the same way. In 2009, a court dismissed a case against AstraZeneca for switching from Prilosec to Nexium. Why? Because Prilosec was still on the market. The court said offering a new version was fine-it didn’t block competition.

But in 2016, the Second Circuit drew a hard line: If you remove the original product, you’re not competing-you’re eliminating competition. That’s why Namenda was ruled illegal. The difference? Availability. If the old version stays, courts often say it’s okay. If it’s gone? That’s antitrust.

This inconsistency is a problem. Some judges still think generics should just “spend more on advertising” instead of recognizing that state substitution laws are the backbone of low-cost access. That mindset lets companies keep playing the game.

Enforcement: What’s Being Done

The FTC and Department of Justice have started pushing back.

In the Namenda case, the FTC got a court order forcing Actavis to keep selling Namenda IR for 30 days after generic entry. That gave pharmacists time to switch prescriptions. In Suboxone, the FTC won settlements from Reckitt Benckiser and Indivior after proving they used fear and deception to block the tablet version.

The DOJ has also gone after generic manufacturers-for price-fixing. Teva paid $225 million in 2023, the largest criminal antitrust penalty ever for a U.S. drug cartel. Glenmark paid $30 million. These cases show regulators are cracking down on both sides: brand-name companies that block generics, and generic companies that collude to raise prices.

State attorneys general have stepped in too. New York sued Actavis in 2014 and won an injunction. Other states are watching closely.

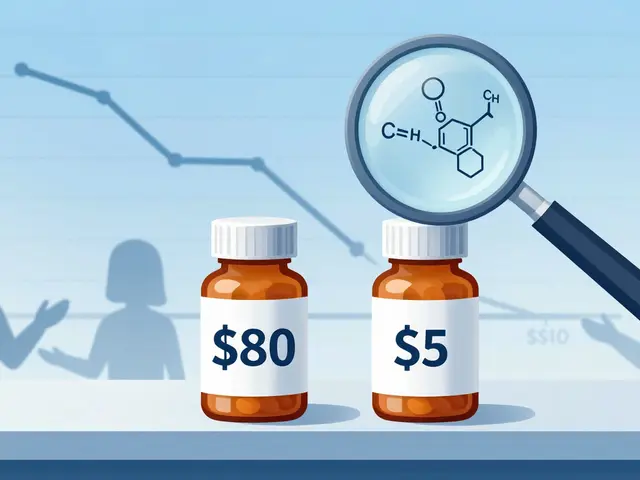

The Real Cost: Billions and Broken Trust

The numbers don’t lie. The FTC estimates that delayed generic entry through product hopping and patent games costs U.S. consumers and taxpayers billions every year.

Take Revlimid. Its price jumped from $6,000 to $24,000 per month over 20 years. A 2023 analysis found that just three drugs-Humira, Keytruda, and Revlimid-cost the U.S. $167 billion more than they would have if generic entry had happened at the same pace as in Europe.

When substitution works, generics take over 80-90% of the market within months. When product hopping blocks it? That number drops to 10-20%. That’s not just a price difference-it’s a health equity issue. People skip doses. They ration pills. They go without.

What’s Next? More Scrutiny, Maybe Reform

The FTC’s 2022 report was a wake-up call. Chair Lina Khan made it clear: product hopping won’t be ignored anymore. In 2023, the DOJ and FTC held joint hearings focused on barriers to generic and biosimilar competition.

Legislators are paying attention. Congress is considering bills to limit REMS abuse and require companies to provide samples to generic manufacturers. Some experts predict new laws will force companies to keep original products on the market for a set time after generic entry.

For now, the message is clear: if you’re a drug company and you’re pulling your original drug off the market to block generics, you’re not just being clever-you’re breaking the law. And regulators are finally catching up.

Virginia Kimball on 14 February 2026, AT 13:09 PM

I swear, if I have to explain one more time to my grandma why her insulin costs $300 when the generic is $20, I’m gonna scream. These companies aren’t innovating-they’re just playing Tetris with patents and leaving real people on the floor. We need to stop treating healthcare like a monopoly board game.