What Is a Hip Labral Tear?

A hip labral tear happens when the ring of cartilage around the socket of your hip joint - called the labrum - gets damaged. This cartilage acts like a cushion and seal, helping keep the ball of the femur securely in place. When it tears, it can cause deep groin pain, clicking, locking, or a sense of instability in the hip. It’s not just a minor nuisance - for athletes, it can end seasons or derail careers.

Most labral tears in athletes aren’t caused by a single injury. They develop over time from repetitive motion, especially in sports that involve twisting, pivoting, or deep hip flexion. Basketball, soccer, hockey, ballet, and long-distance running are top culprits. The real root cause? Often, it’s femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) - a structural mismatch between the ball and socket of the hip that causes the bones to grind against the labrum during movement. Without fixing the underlying FAI, even a surgically repaired labrum has a high chance of tearing again.

Who’s Most at Risk?

If you’re under 40 and active, you’re in the highest-risk group. Studies show that 22% to 55% of athletes with chronic hip pain have a labral tear. Competitive athletes, especially those in sports requiring extreme hip rotation, are hit hardest. A 2022 study found basketball players make up 22% of cases, soccer players 18%, hockey players 15%, and runners 12%. Dancers and gymnasts face even higher complication rates - up to 25% more - due to the extreme ranges of motion they demand from their hips.

Age matters too. Athletes over 35 have lower success rates after surgery, with only 70-75% returning to their previous level of play, compared to 85-90% for younger athletes. Why? Older hips often have early signs of joint wear, making recovery harder. And if you have hip dysplasia - where the socket is too shallow - your risk of re-tear jumps to 60-70% if the structural issue isn’t corrected during surgery.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Diagnosing a hip labral tear isn’t straightforward. You can’t just X-ray it and see the tear. The process starts with a physical exam. Doctors test for pain using two key moves: FADIR (flexion, adduction, internal rotation) and FABER (flexion, abduction, external rotation). If these maneuvers cause sharp groin pain, there’s a 78% chance it’s a labral tear.

Next comes imaging. Plain X-rays come first - they check for bone abnormalities like FAI or dysplasia. But they won’t show the labrum. Standard MRI misses up to 30% of partial tears. That’s why magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) is now the gold standard for diagnosis. MRA injects contrast dye into the joint, making the labrum stand out clearly on the scan. It’s 90-95% accurate at spotting tears, compared to just 35-60% for regular MRI.

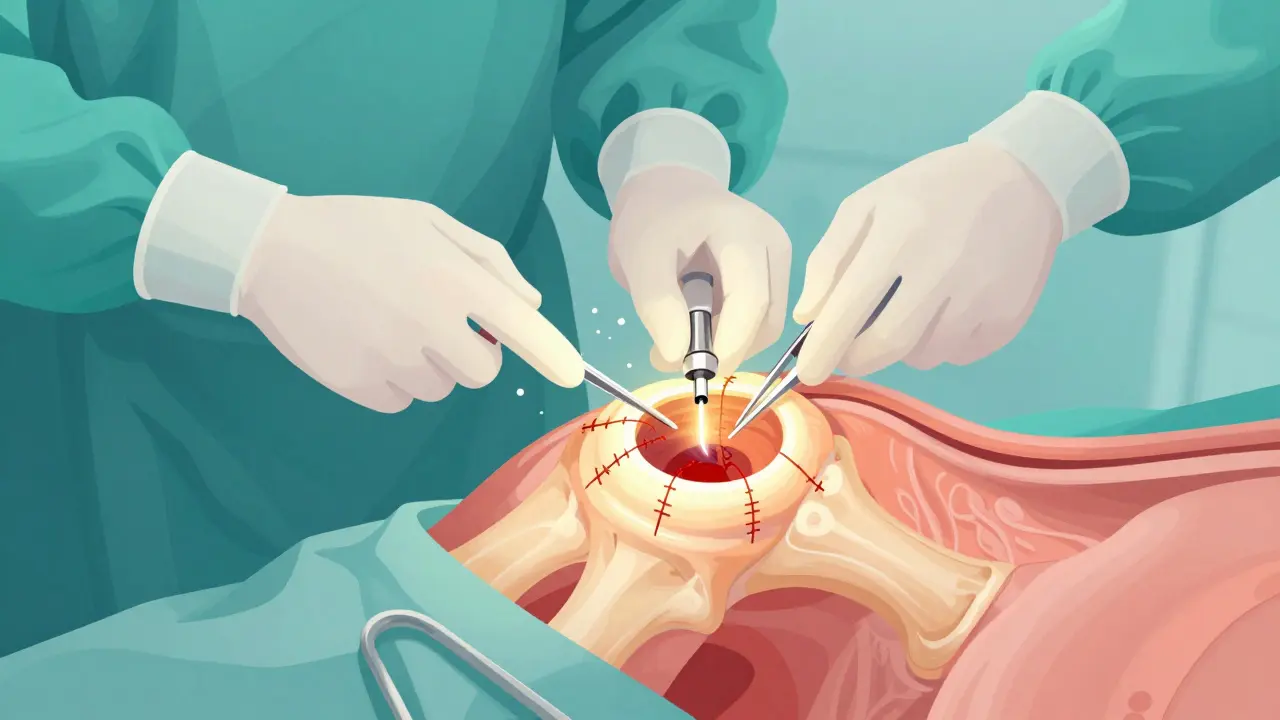

Still, the only way to be 100% sure is arthroscopy. During this minimally invasive procedure, a tiny camera is inserted into the hip joint. It gives direct, real-time visualization of the labrum. Surgeons can see the exact location, size, and type of tear - and fix it at the same time. That’s why many experts consider arthroscopy the definitive diagnostic tool, not just a treatment.

Can You Avoid Surgery?

Yes - but only in some cases. Conservative treatment is always tried first. That means 4-6 weeks of rest, avoiding activities that aggravate the hip, and using NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen to manage pain and inflammation. Physical therapy is next. It’s controversial because studies show only 30-40% of athletes get full relief without surgery. But clinics like True Sports Physical Therapy report 65% success rates with tailored rehab programs - especially when they focus on core stability, hip mobility, and muscle balance.

Corticosteroid injections can help too. They reduce inflammation and give temporary relief for 3-6 months in 70-80% of patients. This can buy time to try therapy or plan surgery. But injections don’t heal the tear - they just mask the pain. Relying on them long-term without addressing the root cause can lead to further damage.

For athletes with mild tears and no structural issues, conservative care can work. But if you have FAI or dysplasia, skipping surgery is risky. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons warns that isolated labral debridement (just trimming the tear) without fixing the bone problem leads to 40% higher revision rates. If your hip shape is flawed, the tear will likely come back.

What Does Arthroscopic Surgery Involve?

When conservative methods fail after 3-6 months, arthroscopy is the next step. It’s done through two or three small incisions around the hip. A camera and tiny instruments go in. The surgeon then decides: repair or debride.

Repair means sewing the torn labrum back to the bone using suture anchors. This is preferred when the tissue is still healthy and the tear is in a good location. It’s the better long-term option because it preserves the natural cushioning of the joint.

Debridement means trimming away the damaged part of the labrum. It’s faster and easier, but it removes tissue that helps stabilize the hip. It’s only recommended for small, degenerative tears without underlying structural problems.

Recent advances include FDA-approved bioabsorbable anchors like Smith & Nephew’s BioX. These dissolve over time, reducing the risk of long-term irritation. Early data shows 89% success at two years - better than traditional metal or plastic anchors.

And it’s not just the labrum. Surgeons often fix FAI at the same time by reshaping the bone - removing excess bone from the femoral head (femoroplasty) or deepening the socket (acetabuloplasty). Skipping this step is a leading cause of failed surgeries.

Recovery and Return to Sport

Recovery isn’t quick. It’s a 6-month process broken into phases:

- Protection (weeks 1-6): No weight-bearing on the hip for the first few days. Use crutches. Avoid hip flexion beyond 90 degrees. Focus on gentle motion and swelling control.

- Strengthening (weeks 7-12): Start light resistance work. Focus on glutes, quads, and core. Goal: 90% strength symmetry between both legs.

- Sport-specific training (weeks 13-20): Begin sport drills - cutting, pivoting, jumping - but without full intensity. Work on control, not speed.

- Return to sport (weeks 21-26): Only when you have full, pain-free internal rotation to at least 30 degrees and no pain during sport-specific movements.

Debridement allows return in 3-4 months. Repair takes 5-6 months. NHL player Ryan Nugent-Hopkins took 5.5 months to return to pro hockey after repair. A marathon runner on Reddit returned at 4.5 months - but that’s the exception, not the rule.

Complications happen. About 15-20% of patients still have pain after surgery. Heterotopic ossification (bone growing where it shouldn’t) occurs in 5-10%. Nerve injury is rare (1-2%) but possible. And 8-12% of patients need revision surgery within five years - often because the underlying FAI wasn’t fixed.

What’s New in 2026?

The field is evolving fast. In 2023, the International Hip Arthroscopy Society updated guidelines to recommend 3D MRI for complex cases - boosting diagnostic accuracy to 97%. Regenerative treatments like platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections are showing promise. A 2022 trial found 55% of patients avoided surgery after PRP, though results vary by tear type and location.

Market trends reflect growing demand. Over 150,000 hip arthroscopies were done in the U.S. in 2022 - triple the number from 2010. The global market hit $1.2 billion in 2022 and is projected to grow 12.3% annually through 2028. Insurance coverage remains a hurdle: 68% of patients pay out-of-pocket for MRA, which costs $1,200-$1,800, compared to $500-$800 for standard MRI.

Experts predict that by 2027, 75% of labral repairs will be done entirely arthroscopically - up from 60% today. The goal? Not just to fix the tear, but to preserve the hip for life. Untreated labral tears increase the risk of osteoarthritis by 4.5 times within 10 years. That’s why the focus now isn’t just on returning to sport - it’s on staying in the game for decades.

When to Seek Specialized Care

Not all orthopedic surgeons are equal when it comes to hip arthroscopy. The learning curve is steep - it takes 50 to 100 supervised procedures for a surgeon to become proficient. Athletes treated at specialized sports medicine centers report 92% satisfaction rates, compared to just 75% at general practices.

If you’re an athlete with persistent hip pain, don’t settle for a quick diagnosis. Ask for MRA, not standard MRI. Ask if FAI or dysplasia is present. Ask if the surgeon performs both labral repair and bone reshaping. If you’re told it’s just a “minor tear” and you’re young, active, and in pain - get a second opinion. Your hip might be sending you a warning you can’t afford to ignore.

steve ker on 13 January 2026, AT 05:20 AM

Labral tears? More like athlete overhype. Just rest and stop pretending your hip is a Rolex.