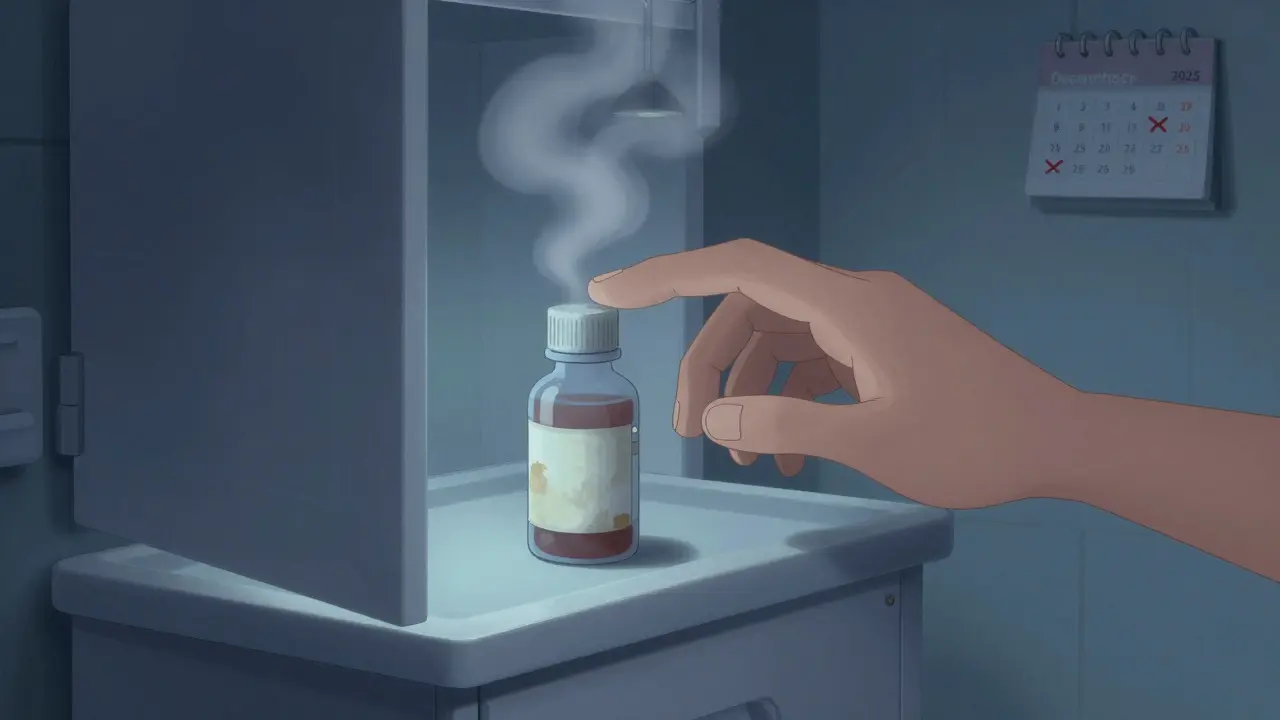

It’s December 2025. Your power’s out. The pharmacy is closed. Your insulin is gone. Or maybe your painkiller ran out, and you’ve got a headache so bad you can’t think. You dig through the back of the medicine cabinet and find a bottle-expired. Three months ago. Six months. Maybe two years. Now what?

Most people panic. Some throw it out. Others take it anyway. Neither is the right answer. The truth is, expired medications aren’t always dangerous-but they’re never safe to treat without careful thought. This isn’t about being scared. It’s about knowing when to use what you’ve got, and when to wait-even if waiting hurts.

Expiration Dates Don’t Mean ‘Dangerous’

Let’s clear up the biggest myth: expiration dates aren’t kill switches. They’re manufacturer guarantees. The date on your bottle means the drug will still work as labeled up to that point, under ideal storage. After that? Potency drops. Safety isn’t guaranteed. But it’s not automatically toxic.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) tested over 100 drugs in its Shelf Life Extension Program. Nearly 90% were still effective 15 years past their printed date-if stored right. That’s not a guess. That’s lab data. But here’s the catch: most of us don’t store meds like the military. We keep them in steamy bathrooms, hot cars, or sunny windowsills. That changes everything.

Not All Medications Are Created Equal

Some expired pills are low risk. Others? Deadly. Your risk assessment starts with the type of drug.

Never use expired:

- Insulin

- Thyroid medications (like levothyroxine)

- Birth control pills

- Anti-platelet drugs (like aspirin or clopidogrel)

- Injectables (epinephrine pens, antibiotics given by shot)

- Liquid medications (cough syrups, eye drops, oral suspensions)

Why? Because these need precise dosing. Insulin that’s lost potency can send your blood sugar soaring or crashing. Birth control that’s weaker? Risk of pregnancy. Antibiotics that aren’t strong enough? They won’t kill the infection-and they might train bacteria to resist future treatment. Liquid meds can grow bacteria. Eye drops? They can cause blindness if contaminated.

On the other hand, solid tablets like ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or antihistamines (Benadryl, Zyrtec) are usually fine for a few months past expiration-if they look normal. Tylenol, for example, may lose up to 20% of its strength after the shelf life ends, but it’s still safe to take. It just might not knock out your headache as fast.

Storage History Matters More Than You Think

You can’t see if a pill degraded. But you can guess. And your guess should be based on where the bottle lived.

If your meds were kept in a cool, dry drawer? Low risk. If they were in a bathroom cabinet, next to the shower? High risk. Humidity breaks down tablets. Heat turns capsules gummy. Light fades colors and alters chemistry.

Research from the PMC journal shows medications stored in humid environments degrade 37% faster than those kept dry. That means a pill that should last 6 months past expiration might fail after just 2 if it sat above the sink for years.

Check for signs of damage:

- Discoloration (yellowing, spots, fading)

- Cracking or crumbling

- Stickiness or melting (especially capsules)

- Unusual smell (rancid, chemical, moldy)

- Particles or cloudiness in liquids

If you see any of these, throw it out. No exceptions. Even if it’s only a week past the date.

Time Since Expiration Is Your Best Clue

How long has it been? That’s your next filter.

For solid oral meds (tablets, capsules) stored well:

- 0-6 months past: Low risk for most non-critical drugs

- 6-12 months: Moderate risk-use only if no other option

- Over 12 months: Avoid unless life-threatening and no alternatives

For liquids, injectables, or critical meds? Even one month past is too long. Don’t gamble.

Providence Health’s clinical guidelines say: if it’s been more than a year, assume it’s unreliable. That’s not fear. That’s data from real patient outcomes.

Use It Only as a Last Resort

There’s no safe way to use expired meds. But there is a safest way-if you have to.

Follow this step-by-step if you’re out of options:

- Check the category. Is it insulin? Birth control? Eye drops? Then stop. Don’t take it.

- Calculate the time. How many months or years past expiration? If it’s over a year, skip it unless it’s a mild painkiller and you’re desperate.

- Inspect it. Look, smell, feel. Any weirdness? Trash it.

- Assess the need. Is this for a fever? A headache? A life-threatening infection? Only consider expired meds for minor symptoms. Never for infections, heart issues, or seizures.

- Use the lowest effective dose. If you take it, start with half the normal amount. Watch for no effect. If it doesn’t help in a few hours, don’t double up. That’s when you need real help.

And remember: if you’re pregnant, elderly, immunocompromised, or treating a child, the risks are higher. Even a slightly weakened antibiotic can be dangerous. Don’t risk it.

Why This Is So Hard

The confusion comes from conflicting advice. The FDA says 90% of drugs are safe for years. But Tylenol says its product loses potency after 2-3 years. The CDC warns against liquids. The EU is pushing to extend expiration dates. The World Health Organization says there’s no global standard.

So who do you trust?

Trust the manufacturer’s label first. Then trust the category. Then trust your eyes. And if you’re unsure? Don’t take it.

There’s no home test for potency. No app that tells you if your pills still work. No cheap kit you can buy online. The only tools you have are time, storage history, and physical condition. Use them.

Prevention Is Better Than Risk Assessment

Washington State’s 2023 health report found that 82% of emergency visits involving expired meds could’ve been avoided. How? By rotating your medicine cabinet every 6 months. Tossing out what you don’t use. Buying only what you need.

Set a reminder on your phone: every June and December, go through your meds. Check dates. Throw out the old ones. Don’t hoard. Don’t keep “just in case.” That’s how you end up with a bottle of 5-year-old antibiotics and no idea what to do with it.

And if you’re in a remote area, or worried about emergencies, talk to your pharmacist. Some offer free disposal programs. Others can help you stockpile stable, long-lasting meds for emergencies-like a small supply of ibuprofen or antihistamines with clear expiration dates.

What If You’ve Already Taken It?

If you took an expired pill and feel fine? You’re probably okay. But watch for:

- No improvement in symptoms

- Worsening symptoms

- Unusual side effects (rash, nausea, dizziness)

If you took insulin, thyroid meds, or antibiotics and feel worse? Seek help immediately. Don’t wait. Sub-potent meds can delay real treatment-and that’s when things turn dangerous.

And if you’re ever unsure? Call your doctor. Or poison control. In Australia, it’s 13 11 26. In the U.S., it’s 1-800-222-1222. They don’t judge. They just help.

What’s Coming Next

The FDA is researching handheld devices that could test drug potency at home using light spectroscopy. Imagine scanning your pill with your phone and getting a readout: “85% potency.” That’s not science fiction-it’s in development.

Until then? Your best tools are knowledge, caution, and discipline. Don’t rely on expired meds. But if you’re stuck? Know how to make the safest choice.

Medicines are meant to heal. But they can hurt if used wrong. The goal isn’t to scare you. It’s to help you make smart calls when there’s no perfect option.

Can expired medications make you sick?

Yes, but only in specific cases. Expired liquid medications, eye drops, or injectables can grow bacteria or break down into toxic chemicals. Antibiotics that have lost potency can cause treatment failure and lead to antibiotic resistance. Solid tablets like ibuprofen or acetaminophen rarely cause direct harm, but they may not work at all. The biggest danger is assuming they still work when they don’t.

Is it safe to take expired painkillers like ibuprofen or Tylenol?

If they’re only a few months past expiration and stored in a cool, dry place, they’re usually safe-but less effective. Tylenol may lose up to 20% of its strength after the shelf life ends. Ibuprofen can remain stable for a year or more. But if the pills are discolored, cracked, or smell odd, throw them out. Don’t risk it.

What should I do if I have expired insulin?

Never use expired insulin. Even if it looks fine, potency drops unpredictably. This can cause dangerous spikes or drops in blood sugar. If you’re out of insulin, go to the nearest emergency room or urgent care. There are programs that provide free or low-cost insulin. Don’t gamble with your life.

Can I extend the expiration date of my meds?

No. Pharmacists and doctors cannot legally extend expiration dates. The U.S. Department of Defense has extended military stockpiles under strict lab conditions, but this is not possible for home use. There are no approved home methods to test or reset expiration dates.

How should I dispose of expired medications safely?

Mix pills with coffee grounds or cat litter in a sealed bag, then throw them in the trash. Never flush them unless the label says to. Many pharmacies and local councils offer drug take-back programs. In Australia, check with your local pharmacy or visit the National Drug Strategy website for disposal locations.

Are expired medications less effective for children or elderly people?

Yes. Children and older adults are more sensitive to changes in drug potency. A slightly weaker antibiotic might not clear an infection in a child, leading to complications. In elderly patients, reduced effectiveness of heart or blood pressure meds can cause serious events like strokes or heart attacks. Never assume expired meds are safe for vulnerable groups.

What if I’m in a disaster and can’t reach a pharmacy?

In a true emergency-like a natural disaster-use expired solid oral meds only if they’re non-critical (e.g., mild pain, allergies), stored well, and less than a year past expiration. Avoid all liquids, injectables, insulin, thyroid meds, and antibiotics. Call poison control or a telehealth service if you can. Your priority is survival, not perfect treatment. But never use expired meds for life-threatening conditions.

When you’re out of options, the safest move isn’t taking the pill. It’s knowing when not to take it.

Sajith Shams on 18 December 2025, AT 18:40 PM

Let me cut through the noise. The FDA study you cited? It was on military stockpiles stored in climate-controlled vaults. You think your bathroom cabinet is a vault? Lol. If your insulin is expired, you don't 'assess risk'-you drive to the ER or you die. No gray area. Stop romanticizing degradation.