What Immunosuppressants Do - and Why They’re Lifesaving

After an organ transplant, your body sees the new organ as an invader. It’s not being ungrateful - it’s just doing what its immune system was built to do: fight off anything foreign. That’s where immunosuppressants come in. These drugs calm down your immune system so it doesn’t attack the transplanted kidney, heart, liver, or lung. Without them, rejection happens fast - sometimes within days. Today, thanks to these medications, most transplant recipients live for years, even decades, with their new organs.

But here’s the catch: turning down your immune system doesn’t just stop rejection. It also makes you more vulnerable to infections, cancers, and serious side effects. There’s no magic dose. Too little, and your body rejects the organ. Too much, and you risk life-threatening complications. Finding the balance isn’t just medical - it’s personal. It depends on your age, the organ you got, your overall health, and even how well you stick to your pill schedule.

The Four Main Types of Immunosuppressants - and Their Hidden Risks

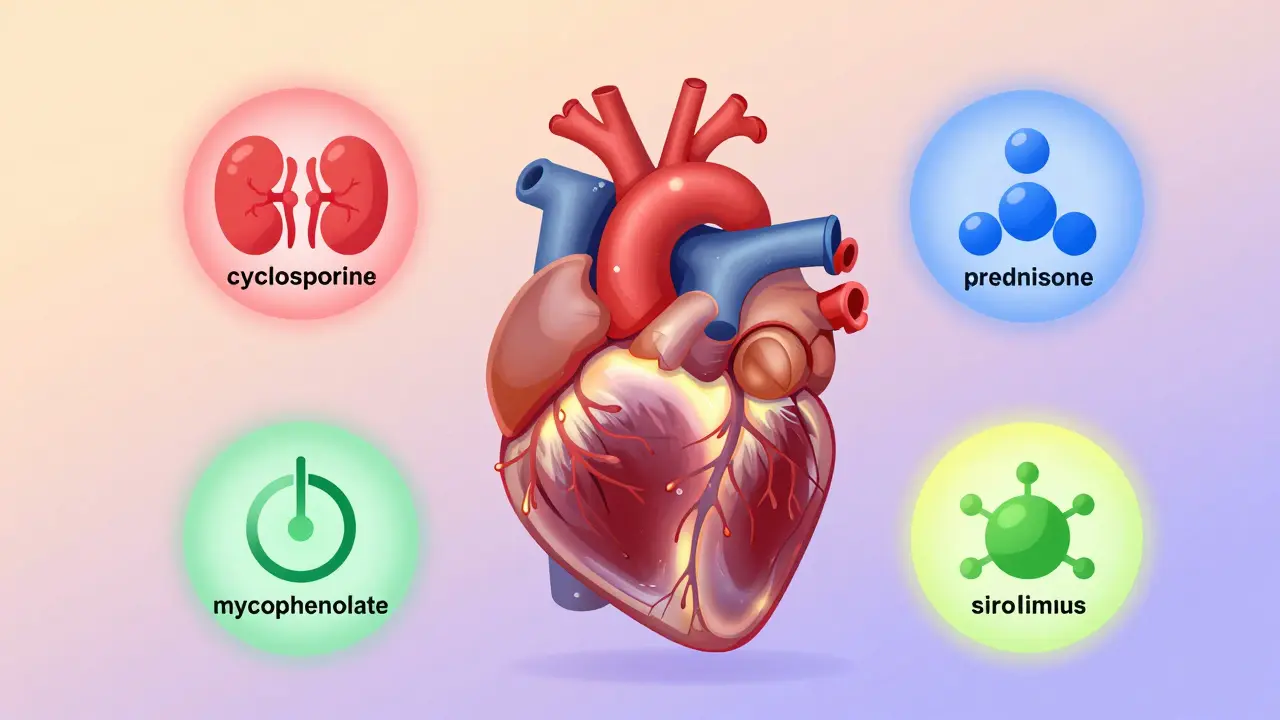

Doctors don’t use just one drug. They combine them. Each class works differently, and each has its own set of risks. Knowing what you’re taking helps you spot trouble early.

Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) - like cyclosporine and tacrolimus - are the backbone of most transplant regimens. They block T-cells, the immune system’s main soldiers. But they’re tough on your kidneys. Up to half of people on these drugs develop long-term kidney damage. They also raise blood pressure, cause shaky hands, and can lead to high potassium or low magnesium. Long-term use increases cancer risk by 2 to 4 times. Tacrolimus is more common today because it’s slightly less toxic than cyclosporine, but it still carries the same dangers.

Corticosteroids - like prednisone - hit the brakes on multiple parts of the immune system. They’re powerful, but they come with a heavy cost. Over time, they can cause diabetes in up to 40% of patients. Bone thinning (osteoporosis) affects 30-50% of long-term users. Weight gain, mood swings, cataracts, and high cholesterol are common. Many doctors try to wean patients off steroids within the first year, but not everyone can.

Antiproliferative agents - such as mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and azathioprine - stop immune cells from multiplying. MMF is preferred because it’s more effective. But it’s hard on the gut. Up to half of patients get nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. About 1 in 5 develop low white blood cell counts, which raises infection risk. These drugs are often paired with CNIs to lower the overall dose needed.

mTOR inhibitors - sirolimus and everolimus - are newer options. They’re less harmful to kidneys than CNIs, making them useful for people with existing kidney damage. But they come with their own dangers. Up to 30% of patients have slow-healing wounds after surgery. About 1 in 20 get a rare but serious lung inflammation called pneumonitis. Everolimus carries a black box warning: it can cause blood clots in the kidney’s main artery, leading to sudden graft loss within the first month. Sirolimus is not used in liver or lung transplants because it’s been linked to higher death rates.

Why Missing a Dose Can Be Deadly

One of the biggest threats to transplant success isn’t a drug side effect - it’s forgetting to take your pills. A study of 161 kidney transplant patients found that 55% weren’t taking their meds as prescribed. Some skipped doses because they felt fine. Others couldn’t afford them. Many just forgot.

This isn’t just about being forgetful. Nonadherence increases rejection risk dramatically. Heart transplant patients who miss doses are 3.5 times more likely to develop transplant coronary artery disease. For kidney recipients, skipping pills doubles the chance of late rejection. And once rejection starts, it’s harder to reverse. Many patients end up back on dialysis or needing another transplant - if they’re even eligible.

Simple fixes help. Switching to once-daily versions of tacrolimus cuts the number of pills in half. Using a pill organizer with alarms, setting phone reminders, or linking doses to daily routines (like brushing your teeth) can boost adherence by 15-25%. If cost is an issue, talk to your transplant team. Many drug manufacturers offer patient assistance programs.

Protecting Yourself From Infections and Cancer

With your immune system turned down, everyday germs become threats. That’s why most transplant patients get antibiotics, antivirals, and antifungals for the first 3 to 6 months after surgery. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common viral threat. If you got an organ from a donor who had CMV and you didn’t, your risk of infection jumps to 70% without preventive treatment.

Regular blood tests check for CMV, Epstein-Barr virus, and other bugs. You’ll also be screened for skin cancer and lymphoma - both more common after transplants. Wear sunscreen daily. Avoid tanning beds. Check your skin monthly for new moles or sores that won’t heal. Report anything unusual to your doctor right away.

Simple habits matter. Wash your hands often. Avoid crowded places during flu season. Wear a mask if you’re around sick people. Don’t clean cat litter boxes or handle soil without gloves - fungi in dirt can cause serious lung infections. Avoid raw or undercooked meat, unpasteurized cheese, and sushi. Even a harmless-looking salad can carry bacteria your body can’t fight anymore.

Monitoring and Adjusting - It Never Stops

Transplant care isn’t a one-time event. It’s a lifelong process. Blood tests check drug levels weekly at first, then monthly, then every few months. Too high? You risk kidney damage or nerve problems. Too low? Rejection looms. Your doctor adjusts doses based on these numbers, not just how you feel.

Some centers now use biomarkers - tiny signals in your blood that predict rejection before symptoms show. This lets them reduce drug doses in low-risk patients without increasing danger. It’s not available everywhere, but it’s the future.

Over time, your regimen may change. After the first year, most people drop from 3-4 drugs to 2-3. Steroids are often phased out. Some patients switch from CNIs to mTOR inhibitors to protect their kidneys. Others get drug holidays under strict supervision. But you never stop taking immunosuppressants - unless your transplant fails.

What Happens When the Transplant Fails

If your new organ stops working, stopping immunosuppressants becomes the right choice. The drugs no longer serve a purpose - and their side effects still hurt you. But you can’t just quit cold turkey. Stopping suddenly can cause a sudden immune flare-up, leading to fever, swelling, pain, or shortness of breath depending on the organ.

Doctors slowly taper the dose over weeks. You’ll be monitored closely. Your body will need time to rebuild its natural defenses. Some people go back on dialysis or wait for another transplant. Others choose palliative care. The decision is deeply personal and should be made with your care team - not alone.

The Bottom Line: Safety Isn’t Optional

Immunosuppressants give transplant patients years they wouldn’t otherwise have. But they’re not harmless. Every pill carries risk. The key isn’t avoiding side effects - it’s managing them. Know your drugs. Track your doses. Report symptoms early. Show up for every appointment. Your survival depends on it.

There’s no perfect drug. But with careful monitoring, smart choices, and strict adherence, you can live well with a transplanted organ - for a long time.

Can I stop taking immunosuppressants if I feel fine?

No. Feeling fine doesn’t mean your immune system isn’t quietly attacking your transplant. Most rejection episodes have no symptoms until it’s too late. Stopping these drugs without medical supervision almost always leads to organ failure. Lifelong use is the norm for nearly all transplant recipients.

Which immunosuppressant has the least kidney damage?

mTOR inhibitors like sirolimus and everolimus cause less kidney damage than calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine and tacrolimus). But they come with other risks - like poor wound healing and lung inflammation. Your doctor will choose based on your overall health, organ type, and risk factors.

How do I know if I’m having a rejection episode?

Symptoms vary by organ. For kidneys: decreased urine output, swelling, high blood pressure. For liver: jaundice, dark urine, abdominal pain. For heart: fatigue, shortness of breath, irregular heartbeat. For lungs: cough, fever, trouble breathing. But many rejections are silent - detected only by blood tests. Never wait for symptoms. Stick to your monitoring schedule.

Are there any new immunosuppressants on the horizon?

Researchers are working on drugs that teach the immune system to tolerate the new organ instead of suppressing it entirely. These “tolerance-inducing” therapies are still experimental. Some centers are using biomarker-guided dosing to reduce drug exposure safely. While no breakthrough drugs are approved yet, personalized treatment is becoming standard practice.

Can I take over-the-counter supplements or herbal remedies?

No - not without talking to your transplant team first. Many herbs and supplements interfere with immunosuppressants. St. John’s Wort, garlic pills, green tea extract, and grapefruit juice can drastically change drug levels. Even vitamins in high doses can be dangerous. Always check with your pharmacist or doctor before taking anything new.

Gaurav Meena on 31 January 2026, AT 04:33 AM

Just got my kidney transplant last year and this post hit home. I take my tacrolimus like it’s my morning coffee - no excuses. Got a pill organizer with alarms and even set a voice note on my phone that says, ‘Don’t be the guy who loses the gift.’ I’m alive because I didn’t skip a day. You guys got this 💪