When a brand-name drug loses its patent protection, the race to bring the first generic version to market can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars. But here’s the twist: the company that made the original drug can legally launch its own generic version-same pills, same factory, same formula-right when the first generic enters. This is called an authorized generic, and it’s one of the most controversial loopholes in U.S. drug law.

How the 180-Day Exclusivity Rule Was Supposed to Work

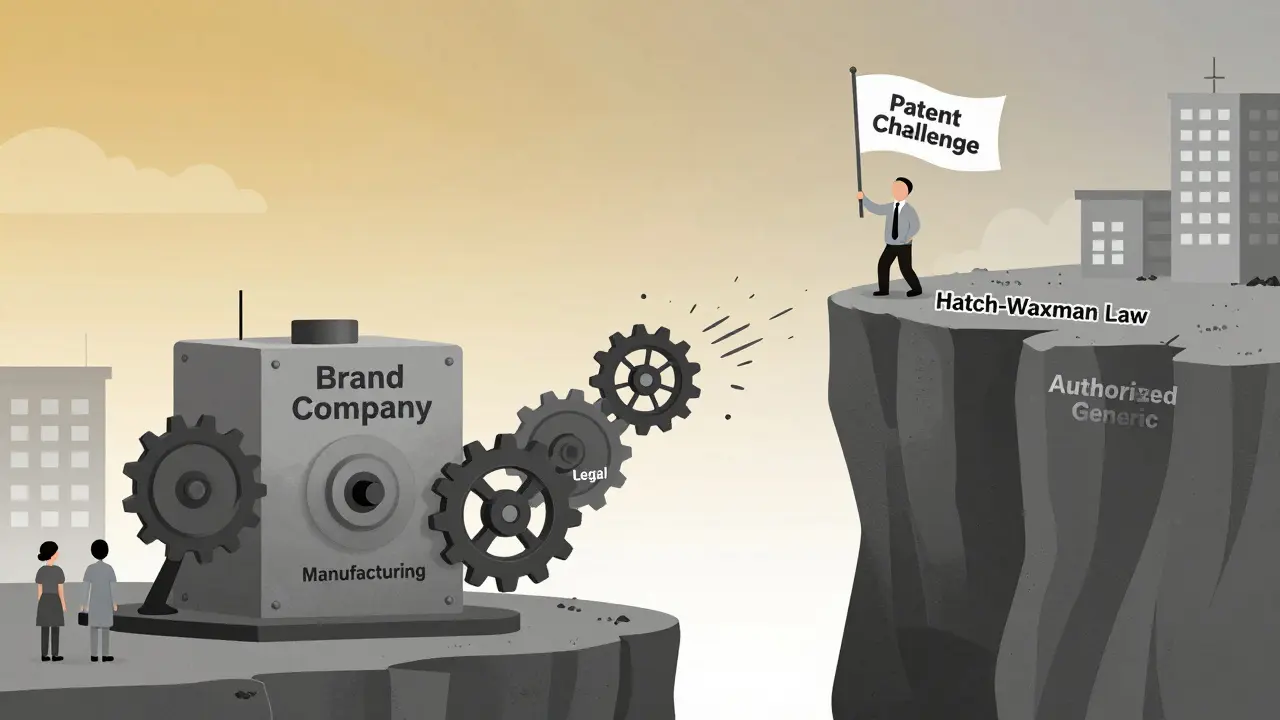

The 180-day exclusivity rule comes from the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. It was designed to fix a broken system. Before this law, generic drugs took years to get approved because they had to redo every single test the original maker did. That made generics expensive and rare. Hatch-Waxman changed that. It let generic companies skip most of the testing if they could prove their drug was bioequivalent to the brand-name version. All they needed was an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). But there was a catch. To make it worth the risk, the law gave the first generic company that challenged a patent a 180-day monopoly. This wasn’t just a head start-it was a full lock on the market. No other generic could get approved during that time. The idea was simple: if you’re willing to spend $2 million on a lawsuit to knock out a patent, you deserve to make all the money from the generic version for six months. That’s how it was meant to work. A generic company files a Paragraph IV certification saying the brand’s patent is invalid or doesn’t apply. They get sued. They fight. If they win, they get the exclusivity. The clock starts ticking the moment they start selling their drug. During those 180 days, they’re the only game in town. That’s when prices drop-fast.What Happened When Brands Got Smart

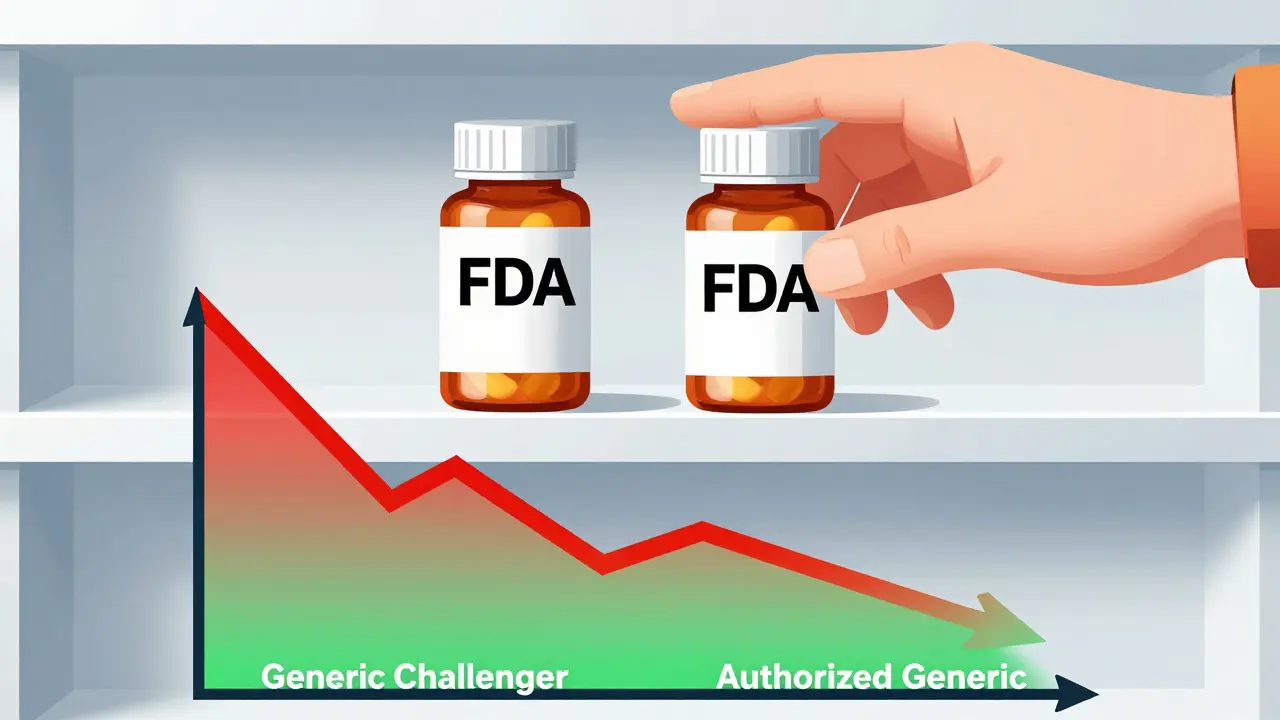

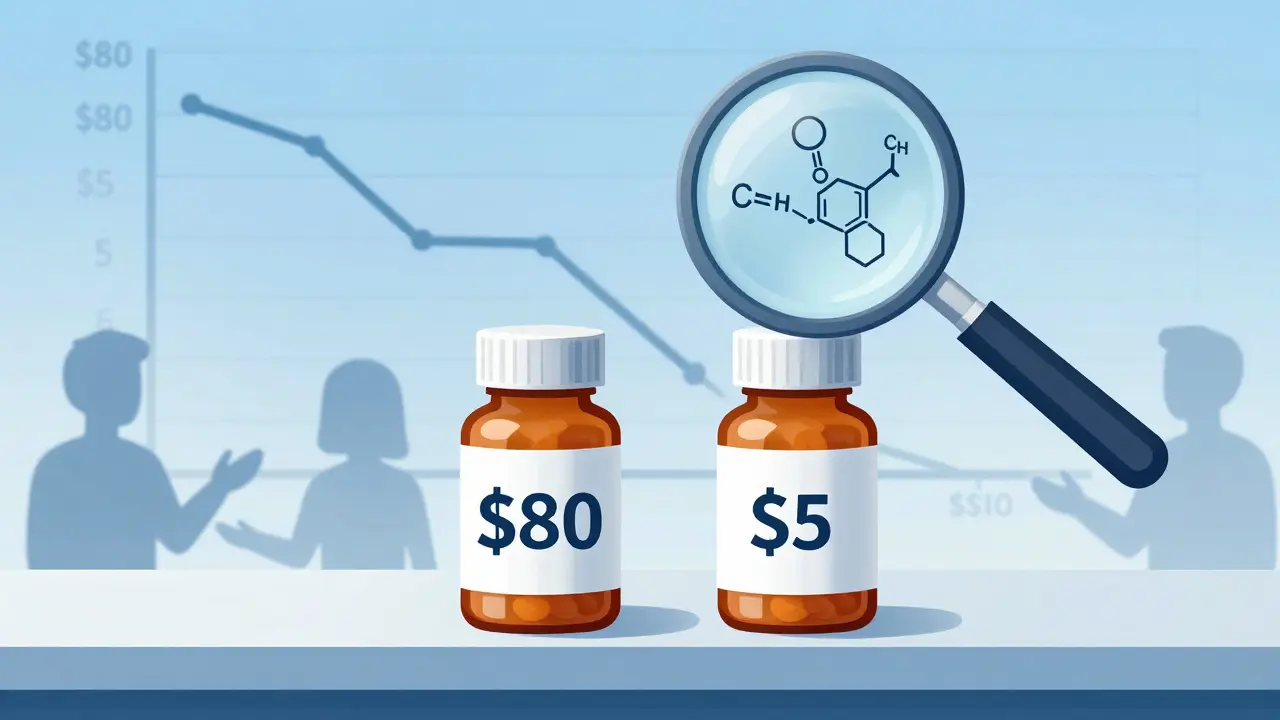

Here’s where things went sideways. Brand-name drugmakers didn’t sit back and wait for generics to eat their lunch. They started making their own generics. Not knockoffs. Not imitations. The exact same pills they’d been selling under their brand name, just without the logo on the bottle. These are authorized generics. They’re made in the same factory, by the same company, with the same ingredients. The only difference? No brand name. No marketing. Lower price. And here’s the kicker: the FDA lets them do this while the first generic company is enjoying its 180-day exclusivity. Legally? Totally allowed. Economically? A disaster for the generic challenger. Imagine this: You spend two years and $3.2 million challenging a patent. You win. You launch your generic. Your sales hit $80 million in the first month. Then, the brand-name company drops its own version-same pill, same price, same shelf space. Suddenly, you’re not the only one selling. You’re competing against the original maker. Your market share drops from 80% to 50%. Revenue? Cut in half. Between 2005 and 2015, about 60% of the time a generic company got 180-day exclusivity, the brand launched an authorized generic. In one case, Teva Pharmaceuticals lost $287 million because Eli Lilly launched its own version of Humalog right when Teva’s exclusivity kicked in. That’s not a mistake. That’s strategy.Why This Isn’t a Flaw-It’s a Feature

Brand-name companies say they’re helping consumers. And they’re not entirely wrong. When an authorized generic enters the market, prices drop even faster. A 2021 RAND Corporation study found that when an authorized generic competes with the first generic, drug prices fall 15-25% more than if only one generic was on the market. That’s good for patients. It’s good for insurers. It’s good for pharmacies. But here’s the trade-off: it kills the incentive for generics to challenge patents in the first place. Why risk $5 million in legal fees and years of litigation if the brand can just step in and take your profits? Smaller generic companies-especially those without deep pockets-have started walking away from these challenges. Drug Patent Watch found that 78% of first generic applicants now include clauses in patent settlement deals that delay or block authorized generic launches. They’re not just fighting patents anymore. They’re negotiating with the very companies they’re trying to compete against.

The Legal Gray Zone

The law doesn’t say you can’t launch an authorized generic during exclusivity. It never has. But that doesn’t mean it’s fair. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has called it a loophole. Between 2010 and 2022, they filed 15 antitrust lawsuits against brand-name companies for using authorized generics to delay competition. They argue it’s a form of pay-for-delay-just disguised as a legitimate product line. The FDA agrees. In 2023, Commissioner Robert Califf told Congress the system creates “unintended disincentives for timely generic entry.” He’s not alone. The Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM) says the original intent of Hatch-Waxman was to give the first challenger a real shot at recouping their investment. Authorized generics undermine that. Meanwhile, the brand-name industry, led by PhRMA, insists authorized generics are consumer-friendly. They point to lower prices and more choices. And they’re right-on paper. The real problem? The law was written for a different world. In 1984, brand-name companies didn’t have the infrastructure to quickly launch their own generics. Today, they do. The system hasn’t caught up.What’s Being Done About It

There’s been a push to fix this for over a decade. Bills like the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act have been introduced in Congress multiple times since 2009. The latest version, reintroduced in 2023, would ban brand-name manufacturers from selling authorized generics during the 180-day exclusivity window. If passed, it could add $150-250 million in revenue to each successful generic challenge. That’s enough to make more companies willing to take the risk. Analysts at Leerink Partners estimate it could increase patent challenges by 20-25%. But it’s not just about money. It’s about trust. Generic companies need to believe that if they win a legal battle, they’ll actually get to reap the reward. Right now, they’re playing a game where the rules change mid-match.

How Companies Are Adapting

Generic manufacturers aren’t sitting idle. They’ve built entire teams just to handle the 180-day exclusivity puzzle. A typical strategy now looks like this:- Start legal prep 18 months before the patent expires.

- Build a cross-functional team: legal, regulatory, supply chain, and commercial.

- Include a clause in settlement talks: “If we win, you don’t launch your own version.”

- Time the launch perfectly-don’t ship product until you’re 100% sure the FDA has approved it.

- Track every shipment. If you stop selling for even a day, the exclusivity clock can reset.

The Bigger Picture

The U.S. generic drug market is worth $65 billion. It fills 90% of prescriptions but accounts for only 23% of total drug spending. That’s the power of competition. And Hatch-Waxman made it possible. Since 1984, the law has helped bring generics to market 3.2 years faster than before. It’s saved the healthcare system $2.2 trillion. That’s huge. But the system is fraying. The authorized generic loophole has turned what was once a powerful incentive into a gamble. And the cost isn’t just financial-it’s access. When smaller generic companies walk away from patent challenges, fewer drugs get cheaper, faster. The question isn’t whether authorized generics lower prices. They do. The question is: at what cost? If the goal is to get more affordable drugs to patients, then the system needs to protect the companies that make that possible. Not let the original makers steal their victory.What’s Next?

Congress is listening. The FTC is pushing. The FDA is signaling support. The pieces are in place for change. But until then, the game continues. Generic companies are still filing Paragraph IV certifications. Brands are still launching authorized generics. Patients are still paying the price-sometimes literally. The 180-day exclusivity rule was meant to be a shield. Instead, it’s become a target.What is an authorized generic?

An authorized generic is the exact same drug as the brand-name version, manufactured by the original company, but sold without the brand name or logo. It’s not a copy-it’s the real thing, just packaged differently. It enters the market during the 180-day exclusivity period of the first generic, undercutting its sales.

How does the 180-day exclusivity period start?

The clock starts when the first generic company begins commercial marketing-meaning the drug is approved by the FDA and actually shipped to customers. It doesn’t start when the company gets approval paperwork. If they delay shipping, they delay their exclusivity. If they stop selling for even a day, they risk losing it entirely.

Why can the brand-name company sell an authorized generic during the exclusivity period?

The Hatch-Waxman Act doesn’t prohibit it. The law only blocks other generic companies from getting approval during the 180-day window. It doesn’t restrict the original brand from selling its own version under a different label. This loophole was never intended but has been legally upheld for decades.

Do authorized generics lower drug prices?

Yes, they do. Studies show that when an authorized generic competes with the first generic, drug prices drop 15-25% more than if only one generic is on the market. But this comes at the cost of reducing the financial incentive for generic companies to challenge patents in the first place.

Is there legislation to stop authorized generics during exclusivity?

Yes. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act (S. 1665/H.R. 3928), reintroduced in 2023, would ban brand-name manufacturers from launching authorized generics during the 180-day exclusivity period. While it hasn’t passed yet, the FDA and FTC both support it as a way to restore the original intent of the Hatch-Waxman Act.

Greg Scott on 19 February 2026, AT 15:08 PM

This is wild. I never realized the brand companies could just slap a different label on their own pills and crush the first generic. It's like they're playing chess while the generics are playing checkers.